Building the STEM economy: Lessons from Massachusetts

Instead of moaning the loss of manufacturing jobs, people from politics to the private sector must focus on creating a strong STEM economy. Technology improves productivity. According to a Ball State University study, of the 5.6 million manufacturing jobs lost between 2000 and 2010, trade accounted for 13 percent of job losses and productivity improvements accounted for nearly 88 percent.

Three factors have contributed to changes in manufacturing employment in recent years: Productivity, trade, and domestic demand. Overwhelmingly, the largest impact is productivity. Almost 88 percent of job losses in manufacturing in recent years can be attributable to productivity growth, and the long-term changes to manufacturing employment are mostly linked to the productivity of American factories. Growing demand for manufacturing goods in the U.S. has offset some of those job losses, but the effect is modest, accounting for a 1.2 percent increase in jobs beyond what we would expect if consumer demand for domestically manufactured goods was flat. — The Myth and Reality of Manufacturing in America

Researchers note that the notion that manufacturing is in decline is “factually incorrect.” Though mixed across sectors, there is solid evidence that manufacturing jobs in primary metals, machinery, transportation, chemicals, and food is growing. The disconnect comes when not considering the rise in productivity among workers due to technology. If the levels of productivity stayed where they were in 2000, we would need 21 million workers in jobs that today require 12 million.

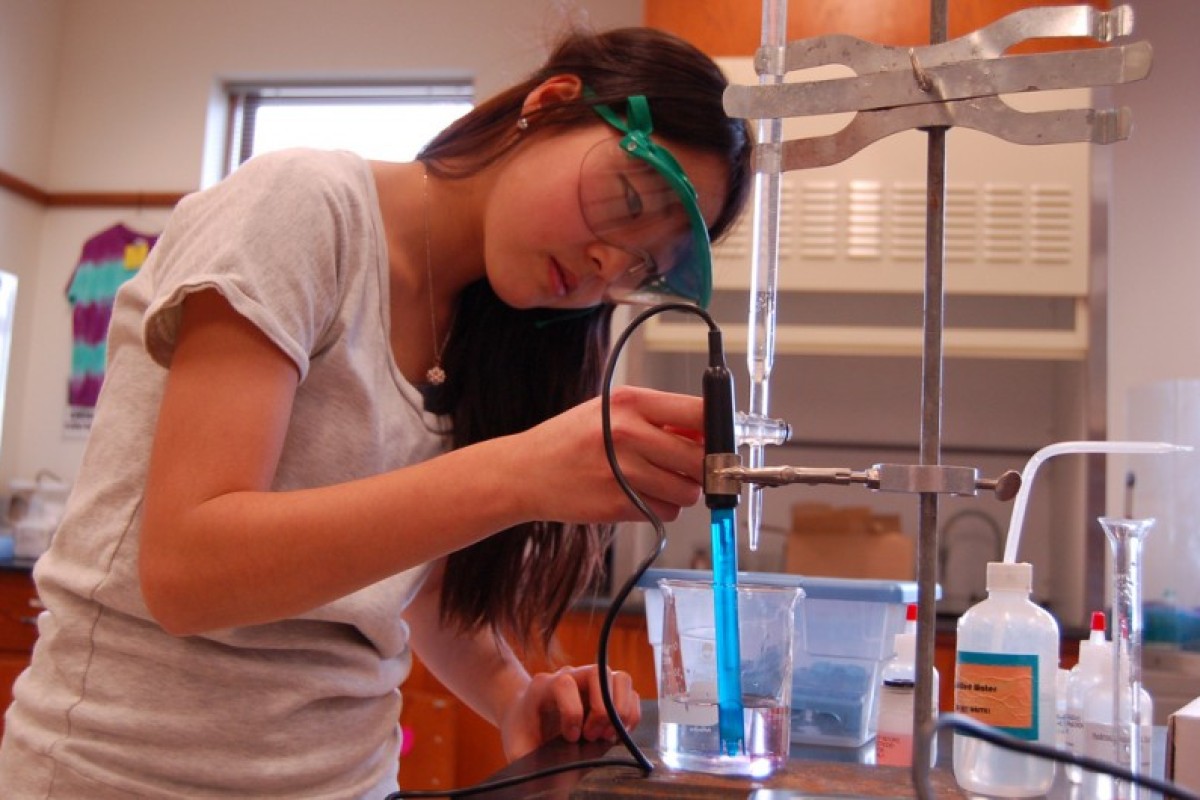

To honestly address the questions of 21st century jobs, especially in manufacturing, we must pay more attention to developing human capital through meaningful reforms from pre-school through post-secondary education. Creating new jobs that recognize the correlation betwenn technological innovation and educational improvement inspired Massachusetts to create the STEM Pipeline Fund.

The Fund emerged from discussions among educators, policymakers and business people at a series of STEM statewide summits in the early 2000s. These discussions raised awareness about the central role of STEM in a successful state economy and inspired representatives from pre-K-12 public and private schools, community colleges, four-year institutions, government, and business to work together to develop a modern workforce.

Former Governor Deval Patrick issued Executive Order 513 in 2009 that identified STEM workforce development as a major state goal. He set up a state advisory council to determine what components constitute a successful STEM pipeline, asking stakeholders throughout the state to critically review existing educational and work programs, looking for redundancies and antiquated approaches to economic development.

The state came up with three components to encourage communication and coordination for a STEM pipeline: STEM regional networks throughout the state, an “at scale” review process to identify best practices, and a STEM strategic plan to support best practices.

At the state level, education commissioners of early childhood education, K-12, and higher education joined together to draft strategic plans to study best practices, set key goals, and develop implementation plans. University of Massachusetts campuses at Amherst and Dartmouth compile and maintain data necessary to evaluate and improve strategic plans. Though the strategic plans have not resulted in systemic realignment, they have provided a common framework and structure for STEM initiatives in the state.

To honestly address the questions of 21st century jobs, especially in manufacturing, we must pay more attention to developing human capital through meaningful reforms from pre-school through post-secondary education.

Sustainable STEM employment growth requires high levels of human capital. We should follow the lead of Massachusetts to build and support targeted education reforms that prepare students for employment opportunities in STEM, especially in the healthiest manufacturing sectors: metals, machinery, automobiles, chemicals, and food.

No Comments Yet!

You can be first to comment this post!