The world in general disapproves of creativity

“The world in general disapproves of creativity,” wrote Isaac Asimov. In a 1959 letter to a team of scientists at MIT, the great science fiction writer advised his colleagues to prepare themselves for disapproval. Creative ideas would appear outlandish and sound ridiculous to most people.

But daring to sound ridiculous when making a new connection among existing knowledge and experience is the essence of creativity. “What is needed,” Asimov wrote, “is not only people with a good background in a particular field, but also people capable of making a connection between item 1 and item 2, which might not ordinarily seem connected.”

Asimov himself understood the process of making unconventional connections. A professor at Columbia University in New York City, he left academia to pursue science fiction writing and is credited with introducing robots and robotics throughout the world. Asimov authored dozens of books, including I, Robot, a tome about robots who could ‘think’.

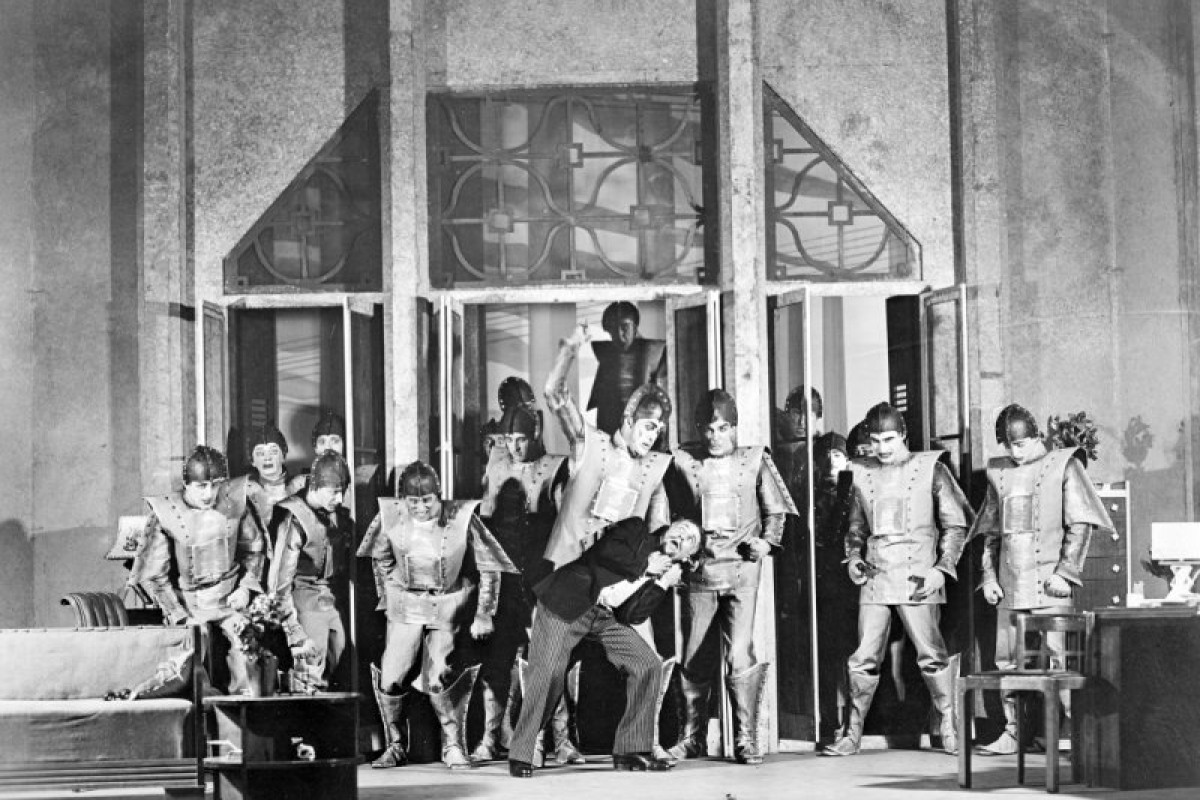

Asimov’s own creativity was inspired by Karel Čapek, a Czech writer of the early 20th century. Čapek first used the word, “robot,” in his play, R.U.R., (Rostrum’s Universal Robots), about an island factory that made artificial people called “robots.” The word itself is derived from the Czech robota, meaning serf labor or drudgery.

Originally published in 1950, I, Robot, and other books by Asimov, had a profound effect on popular culture.

While Čapek’s robots were made of synthetic organic matter (think clones) who eventually destroy humanity, Asimov’s robots helped humanity, doing everything from caring for children to reading minds. Humanity was safe because robots were designed based on three rules:

1: A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm;

2: A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law;

3: A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law;

Asimov had a profound influence on popular culture, inspiring television shows such as Star Trek. But he also inspired scientists who have made the word robot synonymous with modern science and engineering.

Robots became possible in the 1950s and 1960s with transistors and integrated circuits and the invention of electronic computers. Still the stuff of science fiction in the second half of the 20th century, the robot could do everything from threatening good guys and bad guys to inspiring new dance steps.

Today robots paint cars at Ford plants, assemble Milano cookies for Pepperidge Farms, and conduct trains in Paris. Amazon is experimenting with drones as replacements for trucks to deliver goods. Google plans to use robots not only for manufacturing, but also to provide home care for the elderly and disabled. As computer processors are getting faster and cheaper, we can improve robotic movement and ‘thinking’.

Researchers in the United States and throughout the world are designing robot decision-making programs that mimic human decision-making processes. In their book, The Second Machine Age, MIT professors Erik Brynjolfsson and Andy McAfee examine the roles of robots, visualizing robotic ‘thoughts’ as they make up their ‘minds’. The authors present a compelling case that robotics will revolutionize global industry much like the steam engine revolutionized agriculture and manufacturing in the Industrial Revolution. During this “first machine age,” the authors write, a significant number of agricultural jobs vanished. The United States responded by providing education focusing on a new set of skills that led to new occupations.

Nearly half of all U.S. jobs could be automated within the next few decades. As robots get more and more capable, Brynjolfsson notes, “we have to teach this generation of humans a new set of skills. Education in America has focused on getting people to follow instructions. But, going forward, we are going to need much more creativity. Simply following rote instructions is something that software is pretty good at doing.” McAfee adds that the second machine age is all about “overcoming the limitations of our individual minds” through daring to connect things, “which might not ordinarily be connected” — and to share them with others.

That means moving away from individual competition and the inflexible regimen of standardized testing that characterize formal education in the United States. But moving away from the comfortable world of rote to the chaos of creativity is extremely difficult in the formal education system. Research, both in the United States and China, has shown that teachers generally favor quiet, conforming behaviors among their students. This finding would seem to confirm Asimov’s insight more than 50 years ago that “the world in general disapproves of creativity.”

But Asimov’s observation cannot continue to ring true. Like the evolution of the robot from yesterday’s science fiction to today’s scientific reality, embracing the central role of creativity in education and the economy will help discover new skills and occupations that will not only improve our own lives, but the lives of people throughout the world.

No Comments Yet!

You can be first to comment this post!